They are the lost souls of protest, nearly five decades on from an act that was both misunderstood and reviled in its own time and largely forgotten or ignored since, even as it becomes more historically relevant by the day. They were two young Black American athletes – Vince Matthews from New York City and Wayne Collett from Los Angeles, more alike than the distance between their homes, yet different in ways that had defined their pasts, and would shape their futures. They were both fast, both strong. And fearless. Most of all, fearless. They ran the 400 meters, after all, and the track and field event they call the quarter (-mile) is not for the meek.

The race of their lives was the 1972 Olympic 400 meter final in Munich, Germany (West Germany, at the time). At 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 7, eight runners pushed away from starting blocks staggered halfway around the first turn of the rust-colored, all-weather track. Matthews was in lane two, wearing high white socks; Collett next to him in lane three, with no socks at all, and a third American, John Smith, out on an island in lane six. Matthews was the oldest, at 24, and had won a gold medal on the 4X400 meter relay four years earlier in Mexico City (an event that would influence his actions on this evening); Collett and Smith were both 22 and had been competitors at rival L.A. city high schools and teammates at UCLA. It was 55 degrees, with the Bavarian autumn knocking at the door; the stadium was full to its capacity of more than 80,000 spectators. Untethered from concurrent events, it was manifestly just a footrace; but few footraces in history have been more tethered to concurrent events.

The 1972 Summer Olympics remain the most troubled, and tragic, in history. Problems began months before the Games when the International Olympic Committee invited Rhodesia, a nation with apartheid policies, to participate in the Games under the name of Southern Rhodesia, assuming the veneer of a British identity that included “God Save the Queen’’ as its anthem. In response, Black athletes from many African nations promised to boycott the Games. Many U.S. Black athletes also talked publicly of boycotting. Four days before the Opening Ceremony, the IOC voted to exclude Rhodesia. The vote was a narrow 36-31, which allowed resentment to linger.

A week into the Games, U.S. sprinters Eddie Hart and Rey Robinson missed their opening-round heats in the 100 meters and were disqualified, opening the door for Soviet Valery Borzov to win the gold medal (Borzov was an excellent sprinter who might have won regardless, but Hart could motor). There were highlights: Television viewers were charmed by 17-year-old Soviet gymnast Olga Korbut, and U.S. swimmer Mark Spitz won seven gold medals, a record that would stand until Michael Phelps won eight in Beijing, 36 years later. All of this was prologue – and the U.S.A.’s stunning and controversial basketball loss to the Soviet Union on September 10 was epilogue – to the most horrifying episode in Olympic history.

In the early morning hours of September 5, members of a Palestinian terrorist group stormed the Olympic Village, killed two members of the Israeli Olympic team and took nine others hostage. Almost 24 hours later, the nine hostages and a West German police officer were killed during a rescue attempt at a Munich airport. “They’re all gone,’’ ABC’s Jim McKay somberly told his audience, words that endure. The Games were paused only 34 hours, a decision that was controversial at the time, but not the worst of it. The IOC convened a memorial service for the slain Israelis, and IOC President Avery Brundage, an American who left an unflattering legacy, announced to a full stadium, “The Games must go on.’’ Brundage also equated the killing of 11 Olympians by terrorists to the threatened boycott by Black athletes if Rhodesia had been allowed to compete, a metaphor that was insensitive at best, vile at worst.

U.S. marathoner Kenny Moore, who would go on to become a decorated writer at Sports Illustrated, was seated on the infield at the service, and wrote in his 2006 book, Bowerman And The Men Of Oregon, expressing a view that was shared by many athletes: “I recalled being blurry-eyed, staring down at the grass between my feet, and wondering whether I’d heard right. Had Brundage actually just equated the murders of our fellow Olympians with his having to kick out that odious state?’’

It was in this same stadium, scarcely a day later, that runners contested the 400 meters. Their final, as with all Olympic events, had been postponed by a day. They ran through a fog of grief, unmoored from the customary freedom of sport, haunted by the events of the previous 48 hours. In a 1973 interview with the Los Angeles Times’s Jerry Soifer, Collett said, “I walked out onto the track for the finals of the 400 meters and said to myself, `This is the Olympic Games, are you kidding? I’m not even psyched up.’’’ Yet: The Games went on. The race went on, burdened.

Collett had won the U.S. Olympic Trials, with Smith second and Matthews third, but Matthews had looked the best of the three in the Munich preliminary heats (though heats can lie). “We were gonna go one-two-three, the sweep,’’ says Smith, now 70 and the coach of dozens of Olympians and gold medalists since. That was a possibility, but it was Smith whose podium spot was most tenuous; he had tweaked his right hamstring in a pre-Olympic meet (in the Olympic Stadium), and that muscle was on borrowed time. Smith knew it, too. He saw Collett on the warm-up track and told him, “Wayne, it’s yours, go get it.’’ Smith says now, “I think Wayne thought I was trying to pull one over on him, because sprinters will do that on occasion.’’

Eighty meters into the final, Smith was done. He fell to the track at the top of the backstretch. Collett shot past and glanced at Smith. “Keep going!’’ Smith shouted. Did Collett’s glance cost him? It is impossible to know, but one certainty is that down in lane two, Vince Matthews was running a near-perfect race. He had finished fourth in the ’68 Olympic Trials, a painful near-miss that was only partly assuaged by his relay gold. He had waited four years for a second chance, during an era when the onerous demands of amateurism stunted careers. Many days he left his job as a social worker and climbed a 10-foot fence in Brooklyn just for access to a track. This moment was his – he led every step and held off Collett in the final stretch to win the gold medal in 44.66 seconds. Julius Sang of Kenya took the bronze.

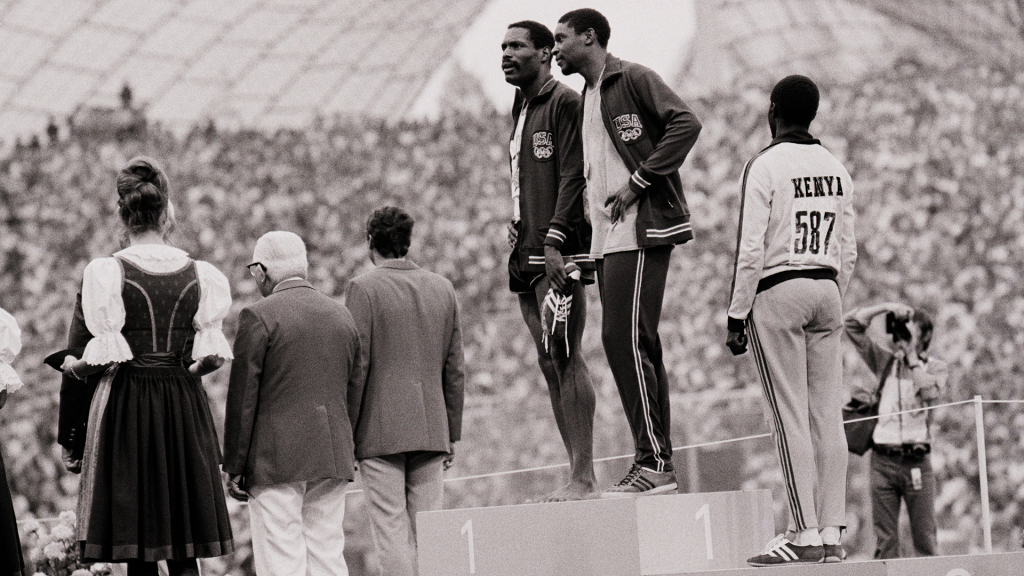

The medal ceremony followed, as ever, and that is where the narrative evolves into something much more significant. The following is described as it occurred, in the moment, without interpretation. That will come later, because it deserves interpretation now that it has only sporadically received since.

Matthews accepted his gold medal while wearing his official sweatsuit, with his jacket unzipped over a grey shirt, sweat-soaked to his upper chest. Collett received his silver medal barefoot, in his racing shorts, with his team sweatsuit top unzipped over his racing singlet. Their dress was decidedly more casual than was customary for a medal ceremony. As the playing of The Star-Spangled Banner began, Collett stepped onto the top step of the victory stand with Matthews; the men were of similar height, about 6-2 – Collett was slightly more muscular, Matthews a little more lean. The two men exchanged words and were alternately smiling and expressionless. Throughout the duration of the anthem, Collett had his hands on his hips while Matthews rubbed his neck and his goatee, crossed his arms and reset his feet.

As Matthews walked off, he removed his medal and twirled it around his finger, like a gym teacher with a whistle. The response in the stadium was instantaneous and visceral as soon as the anthem ended. Dwight Chapin of the Los Angeles Times wrote: “The boos and whistling began when they stepped down.’’ The two men disappeared into a tunnel, and then Collett returned to retrieve his sweats. As he walked away for a second time, he raised his right fist – loosely clenched, elbow bent — while looking up toward U.S. athletes in the stands. There were more whistles.

It all happened in just a few minutes, but would likely become the first sentence in their obituaries. One day after the race, the International Olympic Committee banned Matthews and Collett from the Olympic Games for life, including the 4×400 meter relay in Munich (but did not strip them of their medals). In a letter to the USOC, Brundage wrote: “The whole world saw the disgusting display of your two athletes when they received their gold and silver medals for the 400-meter event yesterday.’’ The USOC asked Brundage to reconsider; he did not. At a contentious meeting in the Olympic village, Jesse Owens was brought in – much as he had been in Mexico City under similar circumstances – and asked Matthews and Collett to apologize; they refused. It was over. Both men went home.

***********************************************

In present-day America, protest unifies and divides, both intensely. This has always been true of real protest, but the last few years have been especially frenetic. Colin Kaepernick first took a knee in 2016, igniting a storm that lives on, culturally and politically, while also compelling important change. At the 2019 Pan American Games, hammer thrower Gwen Berry, who is Black; and fencer Race Imboden, who is white, both protested from the medal stand during the playing of the national anthem (and were reprimanded by the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee). Last summer, Black Lives Matter protests after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police – and the attendant response to the protests – put the country on edge. Professional sports teams – led by the NBA and WNBA — boycotted a night of games in late August to protest the shooting of Jacob Blake by Kenosha, Wisconsin police officers.

Then in December, the USOPC announced that U.S. athletes will be allowed to “peacefully and respectfully’’ demonstrate at future Olympics, “in support of racial and social justice for all human beings.’’ Less than a year after the reprimand, Gwen Berry received a public apology. (To date, the IOC has not adopted a matching policy, although last summer began to explore updating long-standing rules against in-venue protests). It is worth holding all of those things in thought when seeking context on Matthews and Collett, all these years later, because they are as one with the current generation of athletes – and citizens – raising their voices.

In 1972, the immediate media response to Matthews’ and Collett’s medal stand actions was harsh, and, re-examined 49 years later, jarring at best, racist at worst. And since there was no internet and no concept of social media, that response was powerful in shaping public opinion. Matthews’ changing the position of his foot was widely called “shuffling.’’ Collett’s raised fist was called a “black power salute.’’ Typical was a column written by Milton Richman of United Press International, a U.S. wire service with vast reach. Matthews and Collett, Richman wrote, “…. Had just finished 1-2 in the 400-meter final, and now instead of taking their proper positions on the podium, they went into their little act…. They shuffled their feet, stroked their chins, talked with each other and generally conducted themselves as if they were down at the corner candy store.’’ And later: “If you sit down privately with fellows like Vince Matthews and Wayne Collett, you usually find they have a number of grievances, some real, others imagined, just like everybody else. They want theirs, what’s coming to them, and with this all, they want that big word today – respect. But the simplest way of earning respect is to show some first yourself.’’ (Richman died in 1986; he was a highly respected figure in sports journalism, enshrined in the writers’ wing in Cooperstown and twice nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. His writing was of its time).

It was a factor that in the moment after the medal ceremony, Matthews and Collett did little to clarify their actions. “If we wanted to protest, we could do a better job than that,’’ Matthews told reporters. “People are trying to make something out of nothing.’’ Matthews also said their behavior was “a spontaneous thing, a feeling Wayne and I had.’’ Collett did not speak publicly until the day after the race and ceremony. (There was another medal stand moment that is worth recalling for context: several days earlier, Dave Wottle of the U.S. had won a surprise gold in the 800 meters while wearing a golf cap, and also wore the cap during the playing of the national anthem. Wottle apologized and was quickly forgiven. Some Black athletes saw this as a double standard.)

A day after the 400, Matthews and Collett quickly shaped a more forceful explanation for their actions. In an interview with Sam Skinner, a pioneering Black journalist who was working in Munich for a San Francisco radio station, both men described long-held feelings that surfaced emotionally in front of the world.

Collett: “For maybe six or seven years, I’ve stood at attention while the anthem has been played out, but I just can’t do it with a clear conscience any more the way things are in our country. And I just couldn’t do it up there on that stand. There are a lot of things wrong and I think maybe the white establishment has too casual an attitude toward the Blacks of America. They’re not concerned unless we make a little noise and embarrass them.’’

Matthews: “I look at my family, too. I see my father, a bright, smart man with ability that has never come to the surface because of what conditions were like in New York when he was a youngster. He struggled and I’m proud of him for it. It would be hypocritical on my part, wouldn’t it, to stand erect and listen to something like the National Anthem, knowing what my father had to go through in America? When the Star Spangled Banner plays, those conditions come back to you. People are standing at attention and they want you to stand at attention, too, and forget the things around you. It’s impossible.’’

Matthews’ and Collett’s medal stand actions were widely compared to and contrasted with Tommie Smith’s and John Carlos’s iconic display at the ’68 Olympic Games – each wearing the official medal stand uniform, but shoeless in black socks, fists raised skyward, heads bowed. When I wrote about Smith and Carlos for Sports Illustrated in 2018, I asked Dr. Harry Edwards, the sports sociologist who has informed much of the racial activism of the last half-century, what Smith and Carlos contributed most. “Imaging,” said Edwards. “Those two men on a victory podium in Mexico City is the most iconic sports image of the 20th century, and that will still be true 200 years from now.”

Smith and Carlos, gold and bronze medalists engage in a protest in the 200-meter run at the 1968 Olympic Games. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Collett and Matthews contributed an abjectly different image. Interpretation of that image is left to the viewer, but there is one view in which Matthews and Collett created a portrait that while less perfect, was equally powerful – a rejection of the ceremony to mirror the rejection they felt as Black men in the United States. Carlos was in Munich, working for the Puma shoe company. I asked him his view of the Matthews-Collett protest.

“I’ll tell you this,’’ said Carlos. “Vince and Wayne were two young Black athletes who sent the message that Black people were not happy with the way they were treated in America. America made it difficult for them to represent America. Vinny had to jump fences to train. They were saying, `I don’t owe allegiance. America did nothing for me to get here. I had to scrape, scratch and crawl to get to that victory stand.’

“As far as their display,’’ said Carlos, “Theirs was different from ours. Two different images. But think about this: Mr. Kaepernick took a knee. Mr. Smith and John Carlos raised our fists to the sky. Wayne and Vinny twirled some medals and talked. None of those things were threatening, but America felt threatened. That end result was the same for all three.’’

**************************************************

Forty-nine years have passed. Nigh on half a century for a brief moment in time to marinate, as the men involved grew older and the world around them changed. And didn’t change. The question: How did one night in Munich affect the lives of Vince Matthews and Wayne Collett? The answer: More elusive than you might expect.

An Olympic teammate provided me with an email address for Matthews, which I used to request an interview. There was no response (AOL.com so you never know; I kept trying in other ways). A mutual friend contacted Matthews on my behalf and told me that Matthews would not be participating in my story, and also suggested Matthews’ AOL email was working. I tried again. Matthews responded:

“My Olympic participation ended almost 50 years ago. Over the years, I have made a concerted effort to move with an eye toward the future. I live by the following quote `When looking back doesn’t interest you anymore, you’re doing the right thing.’ At this point in my life, the right thing is looking/moving forward and not looking backward.

I hope you will respect my wishes not to be interviewed. Best of luck and success with the story.

Stay safe and healthy.

Respectfully, Vincent.

A week later I asked if Matthews would at the very least provide a life update, without addressing 1972. He did not respond. Matthews is 73 years old; it is only fair to abide by his wish, and to admire it. And his behavior today is consistent with the young man his peers knew, many years ago. “Vincent was reclusive,’’ says John Smith. “That’s who he was.’’ But he has made some elements of his life public, mostly in a 396-page, 1974 memoir called My Race Be Won, with Neil Amdur, then a writer for The New York Times; and in a series of brief interviews he did in 2011, when he was elected to the National Track and Field Hall of Fame, which is located in his native New York City.

My Race Be Won is a fascinating story of a certain kind of life in New York City in the 1950s and 60s and of track and field in the early 1970s, the last days of so-called amateurism and clandestine payments. The book is out of print, but used copies can be had. It is peppered with Matthews’ own poetry; he later created artwork by burning images onto wood panels.

In his book, Matthews tells of his upbringing: He was raised by a father whose family emigrated from St. Kitts and a mother who was born in Detroit, but came to New York from North Carolina, with her grandmother. His first home was a walk-up with cockroaches on the floor and rats in the basement, but through his father’s hard work as a cutter in the Garment District, the family moved to the Marcy Projects in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and then to a six-room house in South Ozone Park, Queens, next to what was then Idlewild Airport, now JFK. He wrote of being nearly knifed by gang members and rousted by police, but also of surviving. He was not precocious; he ran his first 440-yard race in 57.5 seconds as a freshman at Andrew Jackson High School, but by his senior year was city champion and his best time of 48-flat was 19th-best in the country.

In the fall of 1965, Matthews enrolled at Johnson C. Smith University, a Historically Black institution in Charlotte. In college, he experienced the full force of the Jim Crow South. In one chapter, he writes of ordering cheeseburgers with his Black teammates at a diner en route to the Penn Relays, only to be told that they would have to eat them outside. They declined and left the diner, only to find themselves detained by police for not paying for cheeseburgers that they did not want.

Two years after Munich, Matthews wrote even more powerfully of his Munich experience in My Race Be Won. It’s clear from his writing that in ’72 he was deeply bothered by several factors outside the obvious bounds of social justice, not least being an Olympic gold medalist having to climb fences to pursue another gold medal (although there was surely a racial element there). Also, he was discomfited by rumors that, as the third-place finisher in the Olympic Trials, he might be replaced in the 400 by ’68 gold medalist and world record holder Lee Evans. He felt alone. And this also: Matthews and other members of the gold medal 4X400 relay in Mexico City had wrestled with whether to stage a demonstration on the medal stand, a difficult decision in the aftermath of Smith and Carlos. In the end, the relay member (Matthews, Larry James, Ron Freeman and Evans) put their left hand inside their jackets – a nebulous gesture – and stood at attention. “In retrospect,’’ wrote Matthews in his book, “It was clear that all of us harbored some type of fear over possible reprisals.’’

All these thoughts were on Matthews’ mind as he stood on the victory podium in Munich.

As the band struck the last few bars of the national anthem, “… land of the free, and the home of the brave,’’ I was standing there just being myself. That was the way I felt about the whole program. I had zeroed everybody out. There were just a few people who had helped me get where I was. If I had an opportunity, I would congratulate them and thank them. The rest of the people hadn’t done anything for me. If I stood at attention, I was standing at attention for the whole country. The country was getting the praise for what I had done…. ‘’

Three pages later Matthews quotes from James Baldwin’s essay, “Nobody Knows My Name’’: “Any honest examination of the national life, proves how far we are from the standard of human freedom with which we began.’’ And then he added, in his own voice:

I had run my race, but what had my race, the black race, won?’’

In the years following Munich, Matthews rarely talked expansively about that moment, even during a short career in professional track. One exception was a 1980 interview with Frank Barrows of The Charlotte Observer. At the time, Matthews was coaching track at a junior college. He seemed less committed to his past. “Being in the Olympics – or watching them – is a Disneyland,’’ said Matthews. “Certain places you go have a distinct mood – a religious shrine, a football stadium, the Harvard campus. People build a fantasy atmosphere that is very special to them. Maybe escape or retreat is the right word. What I did broke the spell. Which was unpopular.’’

Of the demonstration itself, Matthews said, “I was tired. I had thoughts about Blacks, about America, about how Blacks are treated in America. But I was tired, too. I haven’t wished that I’d been dramatic. I have mixed feelings on whether I’d do it again. It’s a small mystery to me. What happened, happened.’’ It is an unsatisfying answer for those seeking easy truths, as befits a complicated man and a complicated moment.

Upon his election to the Track Hall of Fame in 2011, Matthews did an interview with Elliott Denman, a longtime track writer and himself a 1956 Olympian. Denman wrote that Matthews had long owned an antiques store in Mount Vernon, New York and had been married to his wife, Shirley for 37 years. On the subject of Munich, Matthews created a little more distance from the intensity of the moment: “People were whistling and booing,” Matthews remembered. “They brought on a whole big storm. They made way too much of it. They equated what we did with Tommie Smith and John Carlos in 1968. It wasn’t that at all, but the world saw it differently.’’ He seems to have said nothing publicly since. Remember what he wrote to me: “At this point in my life, the right thing is looking/moving forward and not looking backward.’’

Wayne Collett’s story can be told more clearly, yet heartbreakingly. Collett was diagnosed with nasopharyngeal cancer in 2006 and died of complications from the illness on March 17, 2010, at the age of 60, survived by his wife of 38 years, Emily Stevens; and two sons, Aaron and Wayne II. His medal stand protest from 1972 was, indeed, in the first sentence of his obituary in both The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. The moment followed him, as the moments will most assuredly follow Matthews, Smith and Carlos. But there was much more to Collett than those few minutes.

I connected with the Collett family through Wayne II, 38, who arranged for a video call with his mother, brother and two of Wayne’s lifelong friends, Joe Rippinger and Alex Dubelman. We talked on a Friday afternoon; the call was sweet, sad, moving. Emily, 72, was at first reticent. “I have never talked about these things with anybody publicly, or anybody not really close to me, and hardly any of those people. I’m here because of my sons and it’s important that since you’re going to write this story, that you know this man.’’ She paused. “We’re coming up onto the 11th year since he died. I feel like it was yesterday.’’

Stevens met Wayne in 1971, when both were students at the UCLA Graduate School of Management; they were married a week after Munich and both eventually earned MBAs and law degrees. Stevens worked in the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office until she was appointed as a judge on the Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1987 and to the L.A. Superior Court in 1990, and served there until her retirement in 2010. She says, “That entire time, Wayne was my biggest supporter.’’

In concert with her sons and Wayne’s friends, Stevens described Wayne’s life. He grew up in Gardena, California, an urban municipality just southeast of Los Angeles International Airport, surrounded by freeways; he was the son and only child born to LaCurtis, a native Texan who worked in the U.S. Post Office and later opened a real estate company and Ruth Collett, a stay-at-home mom who later helped out in the real estate business. His life was different from Matthews’ in significant ways, but much the same in this way: The primary force in the home was building a good life for its next generation. Wayne was an excellent student and musician — he played the cello and stand-up bass.

And his athletic skills were exceptional. He went out for track as a sophomore and the first time he ran the 440 he clocked 49.9 seconds, astonishingly fast for a first effort. Where Vince Matthews had to climb from a 57.5 as a freshman, Collett started from a much higher level. As a junior in 1966, he won the California State meet in the 440 (47.8) and his season-best time of 47.2 was second-best in the U.S. (behind Julio Meade, Matthews’ former high school teammate). As a senior in 1967, Collett was fourth in the state meet (47.8 again), and his best time of 46.9 was again No. 2 in the country. I asked John Smith, who was a year behind Collett in high school, if he had raced Collett in prep races. “Yeah I raced him,’’ said Smith. “He beat me into next week. Wayne was a very gifted runner.’’ Collett’s Los Angeles city record of 18.6 seconds for the 180-yard low hurdles will stand forever, as the event is discontinued. (The national record is 18.1 seconds).

It is a subtext of the Munich medal stand story that Collett’s participation was a surprise because many of his peers viewed him as more choirboy than activist. “He was almost a model citizen of what everybody wanted you to be if you were Black,’’ says Smith. But that presupposes that only a certain type of person would engage in public protest of any kind. Collett was indeed an exceptional student, an accomplished musician, a gifted athlete. He was so naturally humble that when he invited Emily on a date to an indoor track meet at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, before their marriage, he didn’t tell her that he was running in the meet; she was stunned when, after the meet, fans lined up for Collett’s autograph. (She also recalls that crooner Johnny Mathis was sitting behind her). In 1971, Wayne was awarded UCLA’s Outstanding Senior Award, which was a campus-wide honor, not limited to athletes. But Collett was more than just those accolades. Also: Tommie Smith would fit the description of choirboy.

In reality, Collett had begun giving thought to the station of Black men and women in American long before Munich. “Years before that,’’ says Joe Rippinger, who was Collett’s roommate and close friend at UCLA, “He would not stand for the national anthem at UCLA basketball games. He was being consistent with that behavior in Munich.’’ (This does not square with Collett’s comment to Sam Skinner in Munich, that he had been standing uncomfortably for years, but Rippinger says his story is true. Also, Stevens says that Collett did not stand for the anthem for a period after Munich. I asked if that period was “months, or years?’’ Stevens said, “Not months.’’ It was apparently a position that he held before, during, and after Munich). Wayne II and Aaron both said that later in his life, Collett stood for the anthem at Raiders, Lakers and Dodgers’ games, of which they attended many together, as a family.

Collett used his law degree to engage with the real estate community and most forcefully to assist poor, minority home buyers in securing reasonable loans. It was hard, honorable work that his family says he relished. When Wayne died, Emily heard from several people who recounted his role in their lives. “So much I didn’t know, because Wayne didn’t bring his business home,’’ says Emily. “One woman told me, `Wayne saved my life, more than once.’ I learned that he helped get loans, but loans that they could handle, and that wouldn’t make them worse off… if the rate changed.’’ Collett also worked for the Los Angeles Olympic Committee in 1984, a celebratory time for the city.

Collett was less reticent than Matthews to share his Munich experience. He was not proactive, but if asked, he would answer. One slice of narrative that emerged was that there was another piece to Collett’s mindset upon arrival in Munich. Prior to the Olympics, U.S. Track coaches convened a three-week training camp at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. Collett preferred to remain in Los Angeles with his coach, UCLA’s Jim Bush. He was told that attendance was mandatory. Emily Stevens read to me from unpublished sections of a letter written by Bush to the Los Angeles Times at the time of Collett’s death. “ The Olympic coaches called him to report within 24 hours,’’ wrote Bush. “Or he wouldn’t be allowed to compete on the relay team, while other athletes were allowed to stay with their coaches to the last minute. Wayne took it personally. He called me very upset. Unfortunately, I couldn’t do anything about it. It was politics as usual.’’ Collett carried that moment with him to the 400 final, and to the victory stand.

Around 2000, Wayne Collett accompanied his son, Aaron, now 42, to a class at UCLA and spoke about his Munich experiences to a gathering of several dozen people. This is Aaron’s recollection from that class:

“It was the most thorough description I had heard in my life. He talked about Rhodesia, and the idea that you can’t put a veneer on something, without having changed it. He talked about how chaotic those Olympics were, how they rushed [Collett and Matthews] out there to the victory stand and they were on the wrong side of the field and they couldn’t really hear the national anthem. A lot of things were going on. But none of that matters. They asked him to apologize, because America was embarrassed, and he said he would not do that, because [he felt] America was embarrassed because of the way America treats Black people. And America had to look at [Collett and Matthews]. People tried to say my father was un-American. That he was a radical. He wasn’t any of those things. He was a patriot. He believed in the law and the Constitution and in systems. He gave me Roberts’ Rules of Order when I was 12. He believed that America could work, but he would not apologize just because America is embarrassed, without addressing the underlying conditions of African Americans. And now, once again, America is embarrassed at its treatment of Black people.

He said many times, that if he had known what he was going to do that day would make such a big deal, right? He said he would have done more.’’ Think back: for Vince Matthews, there were mixed feelings and a small mystery. Things were clearer for Wayne Collett. One moment, two different men.

(One other point. Collett also told Aaron’s class that his raised fist was not a Black Power salute, per se. “They were rushed off the podium, exiting the opposite side that they entered, so my father had to come back on the field to get his stuff,’’ said Aaron. “He was still processing everything that had just happened, so when the USA track team started clapping for him, it took him by surprise. He said he felt the support of the team and responded reflexively in solidarity. They were there to compete as a team and that camaraderie was what he was responding to.’’)

On the Saturday in 2008 after Barack Obama’s election as President, Collett attended a UCLA football game at the Rose Bowl with college buddies and planted an American flag at their tailgate, something he had never done previously. Two months later, sick and weakened by the cancer, he watched Obama’s inauguration while lying in bed next to Emily. A picture of his father sat on one nightstand, a picture of Emily’s father on the other.

Tim Layden is writer-at-large for NBC Sports. He was previously a senior writer at Sports Illustrated for 25 years.