Never let a good crisis go to waste: it is an adage seemingly attributed, like so many others, to Winston Churchill.

ATRs Olympic role redundant after new hospitality deal, De Kepper confirms

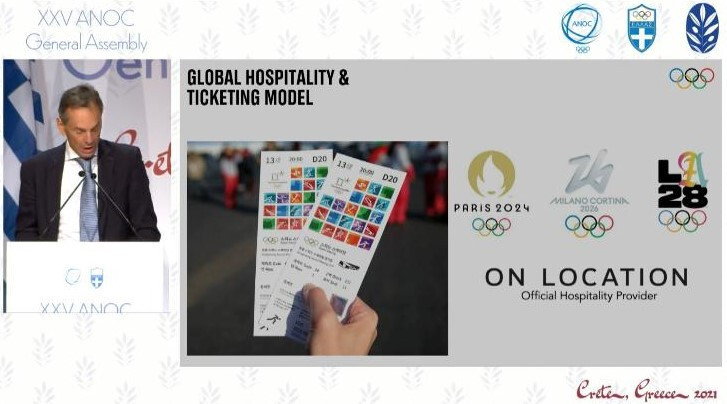

There will be no role for authorised ticket resellers (ATRs) in the future, it was confirmed by International Olympic Committee (IOC) director general Christophe De Kepper here today.

Giant subsidy cut leaves ANOC finances weakened

A savage 70 per cent cut in the Association of National Olympic Committees (ANOC)’s International Olympic Committee (IOC) subsidy has left ANOC’s finances and outlook considerably weakened.

Presentation slides displayed at the current ANOC General Assembly in Crete indicate that the subsidy accounted for more than 97 per cent of the umbrella body’s $55.1 million (£40 million/€47.3 million) income during the 2017-2020 Olympic quadrennium.

ANOC plans to dip heavily into its $20.5 million (£14.9 million/€17.6 million) end-2020 cash balance to make ends meet over the next quadrennium until 2024.

The body has also warned that a "dedicated subvention" would have to be "negotiated if needed" for a second edition of the ANOC World Beach Games.

The first edition, staged in Qatar in 2019, is costed at $23.5 million (£17 million/€20.2 million), of which more than $16 million (£11.6 million/€13.7 million) is said to have been covered by the Qatar Olympic Committee.

ANOC explained that "due to the 25 per cent increase in the budget of [Olympic Solidarity] (OS) to contribute to help the National Olympic Committees (NOCs) following the difficulties due to COVID-19, the OS has significantly decreased the subvention to ANOC for 2021-2024."

It put the total cut at $37.8 million (£27.5 million/€32.5 million) - "or a reduction of 70 per cent compared to the previous quadrennial".

In July 2020, the IOC said it had "already supported" NOCs and International Federations (IFs) with "around $100 million (£73 million/€86 million) since the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis", with $63 million (£46 million/€54 million) allocated to IFs and $37 million (£27 million/€32 million) to NOCs.

Some four months later it announced that OS’s budget for 2021-2024 was being increased by 16 per cent to $590 million (£429 million/€507 million).

The rate of increase for "direct athlete support programmes" was put at 25 per cent.

IOC President Thomas Bach described the uplift as "a very strong demonstration in times of a worldwide crisis".

ANOC had already unveiled a $11.65 million (£8.5 million/€10 million) COVID-19 funding package of its own for NOCs.

The figures unveiled today show that this pushed ANOC to a deficit of $3.575 million (£2.6 million/€3 million) for 2020, and of just over $5.5 million (£4 million/€4.7 million) for the entire 2017-2020 period.

Under the general budget for 2021-2024 presented to the General Assembly, the entirety of ANOC’s $15.3 million (£11.1 million/€13.1 million) of surplus OS funds carried forward, as well as $2.7 million (£2 million/€2.3 million) of its own funds balance are to be deployed to balance the books, given projected expenditure over the four years of $34 million (£24.7 million/€29.2 million).

With ANOC’s fund balance weighing in at just $5.18 million (£3.8 million/€4.4 million) at end-2020, this would apparently leave the body with a projected cash balance of just $2.5 million (£1.8 million/€2.15 million) at end-2024.

Broeksema elected Aruba Olympic Committee President

Wanda Broeksema is the new President of the Aruba Olympic Committee (COA), following an election at the organisation's General Assembly.

ANOC EXECUTIVE COUNCIL MEETS AHEAD OF FIRST EVER CARBON NEUTRAL ANOC GENERAL ASSEMBLY

The ANOC Executive Council met in Crete today to discuss a number of important reports and initiatives ahead of what will be ANOC’s first carbon neutral General Assembly.

Onesti's vision of uniting the world's NOCs which laid the path for ANOC

A few days after witnessing the lighting of the Beijing 2022 Olympic Flame, International Olympic Committee (IOC) President Thomas Bach is set for more duties in Greece at the Association of National Olympic Committees (ANOC) General Assembly in Crete.